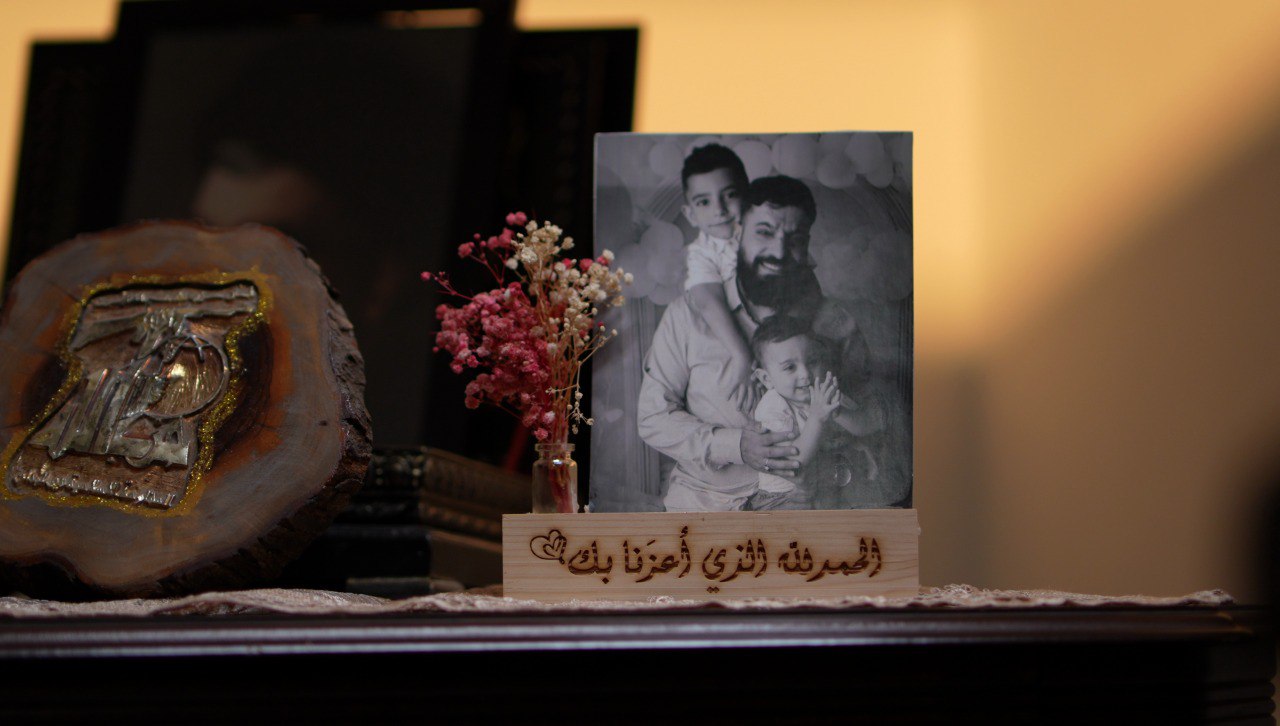

Abu Haidar, Abu Ali, and his wife lost parts of their bodies… but they didn’t lose their hunger for life.

Everything changed: their bodies, their eyes, even their daily plate of food.

Food now had to follow a medication schedule, and the sound of the spoon became a daily reminder.

And yet, they resisted.

They no longer waited for full recovery — instead, they crafted a new balance between what was whole and what was missing, between what they had lost and what still carried their name.

This is not just a story about a war that tore the body apart — it’s a story about a human being who reorganized his life around the table, with patience and a heart beating with resistance.

“I was just going out to get a bag of bread,” he says in a voice that still holds traces of disbelief.

“I heard the sound… my eyes shut. I felt my body become light — then unbearably heavy.”

That moment, just before the explosion, replays in his mind every day.

He remembers how his hand used to move effortlessly. How he could fry two eggs without thinking.

“There’s no such thing as automatic anymore. Everything takes time, focus, and patience.”

After the injury, Abu Haidar underwent multiple surgeries.

His arm was amputated below the shoulder. Both his eyes were damaged. He received intensive physical therapy to learn how to use his body again.

But the wound wasn’t just in the body.

“I used to feel ashamed to eat in front of others. I felt like a burden, and I would leave the table and sit alone.”

The feeling of helplessness crept from the spoon into his heart, and from the wound into people’s eyes.

And because wounded individuals are often seen as silent heroes in society, expressing weakness wasn’t easy.

But he found a way back — through food. A small door, but enough to begin again.

A nutritionist entered his life like someone entering a dark room and switching on a tiny light.

“We’ll start from scratch,” she said simply.